This post comes to us from Discovery Fellow Chrishann Walcott

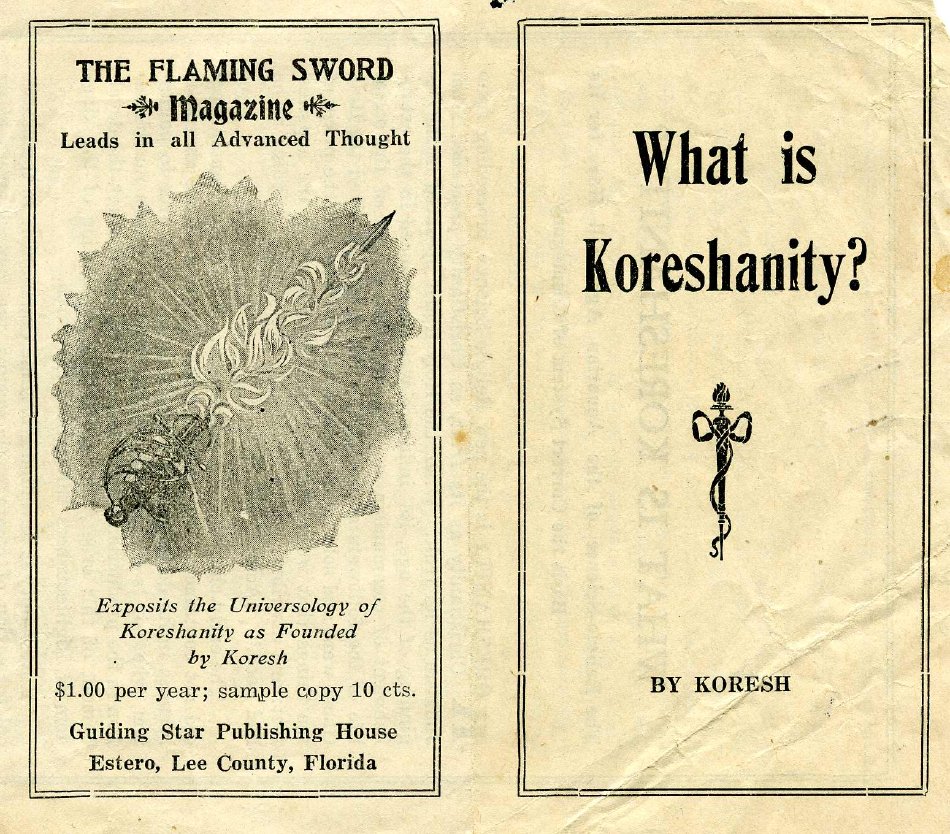

As the semester concludes, I’d like to take a reflective glance at the materials that I have come across in the Special Collections. At the beginning of my research, I intended to focus more on the influence of two major religions—Judaism and Christianity—on politics and culture in America during the early 20th century. After taking a deep dive into Koreshanity, I became interested in investigating the so-called “offshoots:” religious and spiritual communities that classified as utopias, as documented by late 19th and early 21st century materials.

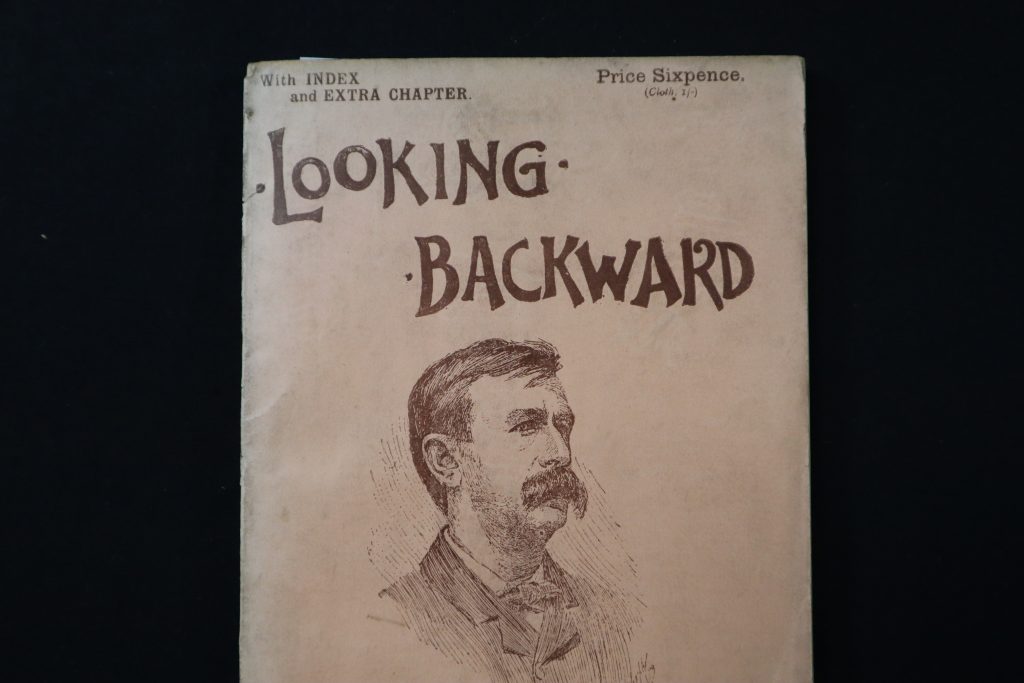

Now, what is a utopia? Edward Bellamy’s 1888 fiction novel “Looking Backward,” depicts a utopia as a state of collectivism in which society has reached its ideal state. Bellamy’s ideas were a response to the volatile sociopolitical reform movements of the late 19th century. Some of these ideas have flowed into the principle of communitarianism that had become central to the foundation and maintenance of many of these utopian communities. Utopian communities are bound together through a collective mutual identity, whether that identity is spiritual or political.

Spiritual utopian communities, in particular, mark their communes as sacred spaces, usually isolated or physically demarcated from the rest of the world. In the post-civil war era, Spiritualist movements blossomed as many wished to reconnect with their deceased loved ones, something that they could not do under the restraints of traditional Protestantism, but could do with the help of spiritual mediums who act as intermediaries between the physical and spiritual world. Furthermore, the age of Spiritualism coincided with the women’s rights movements, and thus women played a crucial role in the movement by gaining authority as spiritual mediums.

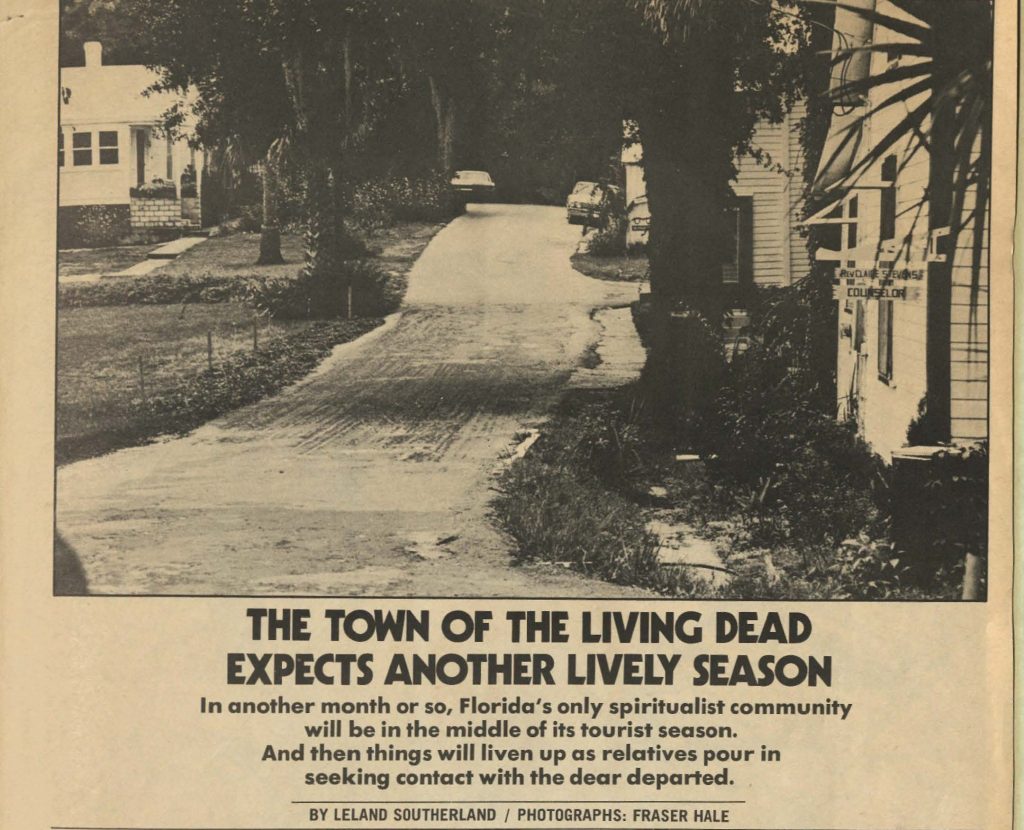

In the collections, I came across a 1972 newspaper clipping from The Floridian detailing the activities of a Spiritualist Camp in Cassadaga, dubbed the “Psychic capital of the world”. The commune was established in the mid-1890s by the prominent medium George P. Colby as led by spiritual guides to “…fulfill a prophecy and found a retreat in the wilderness,”—a revelation not uncommon among leaders of communes or religious sects. More communes rose along the East Coast as the movement grew in popularity and believers wished to create a definite structure for their doctrines.

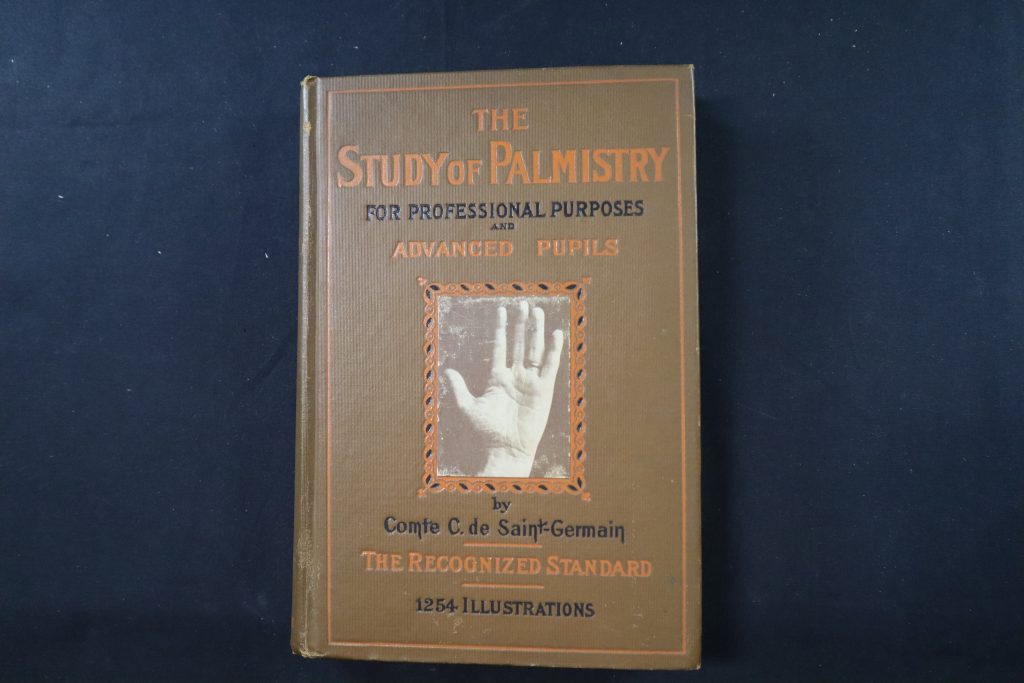

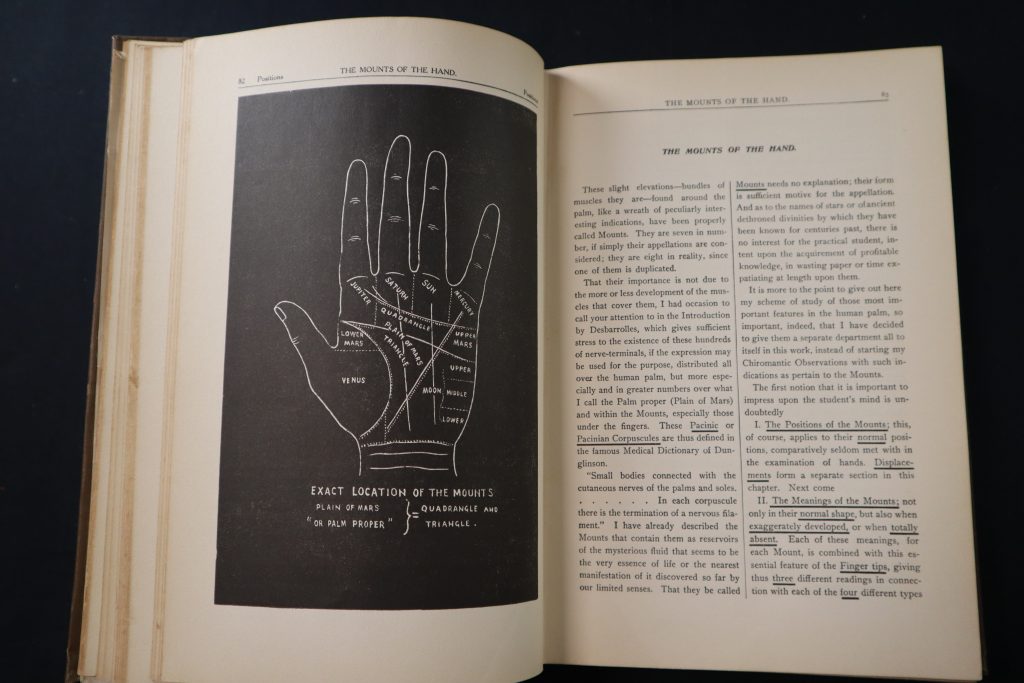

Currently, Cassadaga maintains its status as a community with a set of flexible theologies and is run by trained individuals that provide services such as healing, palm readings, and other means of clairoyance. One subject that I found interesting to dive into was the role that religious commercialization has played in the Spiritualism movement, and in the livelihood of Cassadaga in particular. The commercialization of Spiritualism reinstates a fundamental boundary between devoted believers those who might be hesitant of such practices and seek to exploit followers for monetary gain.

By taking a look backwards at utopian communities within the state of Florida, we can understand how and why certain beliefs and customs have persisted through time—appreciating the spirit of mutual acceptance that binds members together and their stories. This fellowship allowed me to explore how religious and spiritual beliefs in the context of utopian communities have been perceived by the general public and think more critically about how such material is presented in popular culture. In the future, I wish to learn more about other communities that may have been obscured in mainstream history.