As we prepare to welcome our new cohort of Discovery Fellows for 2024, we want to look back at the results of our 2023 fellowship cohort.

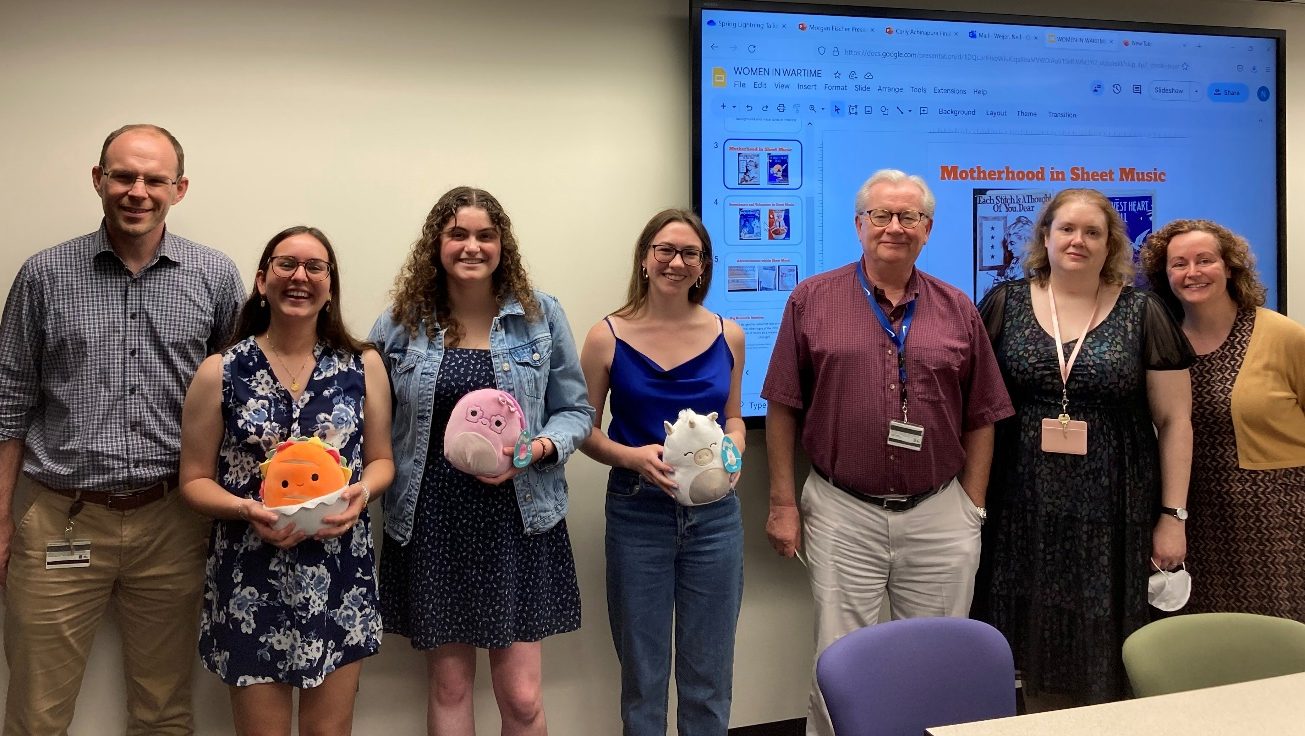

In previous years, students concluded their fellowships by writing a second post for the Storied Books blog. This cohort of students were instead asked to give a five-minute talk about the research topics that they had formed during their work with the collections, followed by the chance to take questions about future research plans and how they might incorporate their experiences into the rest of their undergraduate career. The talks were well attended and included members of the Department of Special and Area Studies Collections, fellows from previous cohorts, and friends of the presenters.

Now let’s hear from the Discovery Fellows about their research questions and how they plan to take their inquiries further.

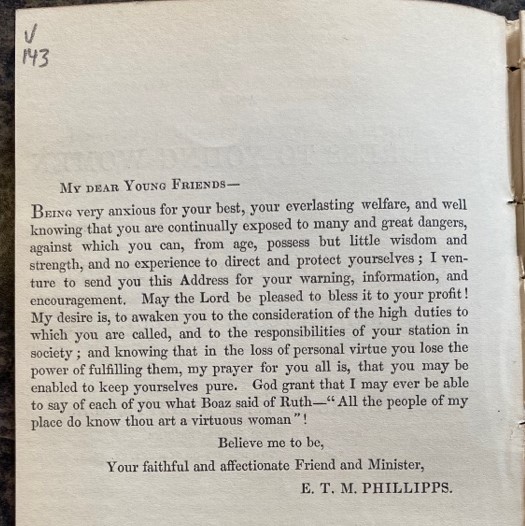

Fallen Women by Carly Achinapura

I’ve come to the question: how do English Victorian perspectives on ‘the fallen women’ in literature affect 20th-century and modern perspectives on prostitution and sex work? In my research, I looked at how women of different socioeconomic statuses in Victorian England would have encountered the idea of the ‘fallen woman’ (or a woman whose loss of her virginity places her on the path to ruin and, oftentimes, death). I started by reading small, cheap pamphlets aimed toward lower- and middle-class women that gave insight into Victorian ideas of virtue, chastity, and ‘fallenness’. Other items I consulted included conduct literature and philanthropic works on prostitution kept in microform, which would have been aimed at middle- and upper-class women.

This summer and fall, I’ll be writing an honors thesis. I’m looking into The Chimes by Charles Dickens and observing the way Dickens excuses the suicidal ideation of the fallen woman while simultaneously shaming the prostitute. This is such an important novel due to its criticism of upper-class values and attitudes towards the lower class, criticism of upper-class philanthropic institutions and their effectiveness, and its questioning of whether the poor can truly be helped and/or redeemed. The observations that I have made in my research here are going to help me in the contextualization of my thesis, as I have a better understanding of ‘fallenness’ from a series of socioeconomic perspectives. This would answer the question I’ve posed as Dickens is one of the most canonized authors of 19th century England. His ideas influence audiences in the 20th and 21st centuries and affect the way people look at the past prostitute and the modern sex worker: as either a person to be helped or a problem to be solved.

The Many Faces of Children’s Books by Morgan Fisher

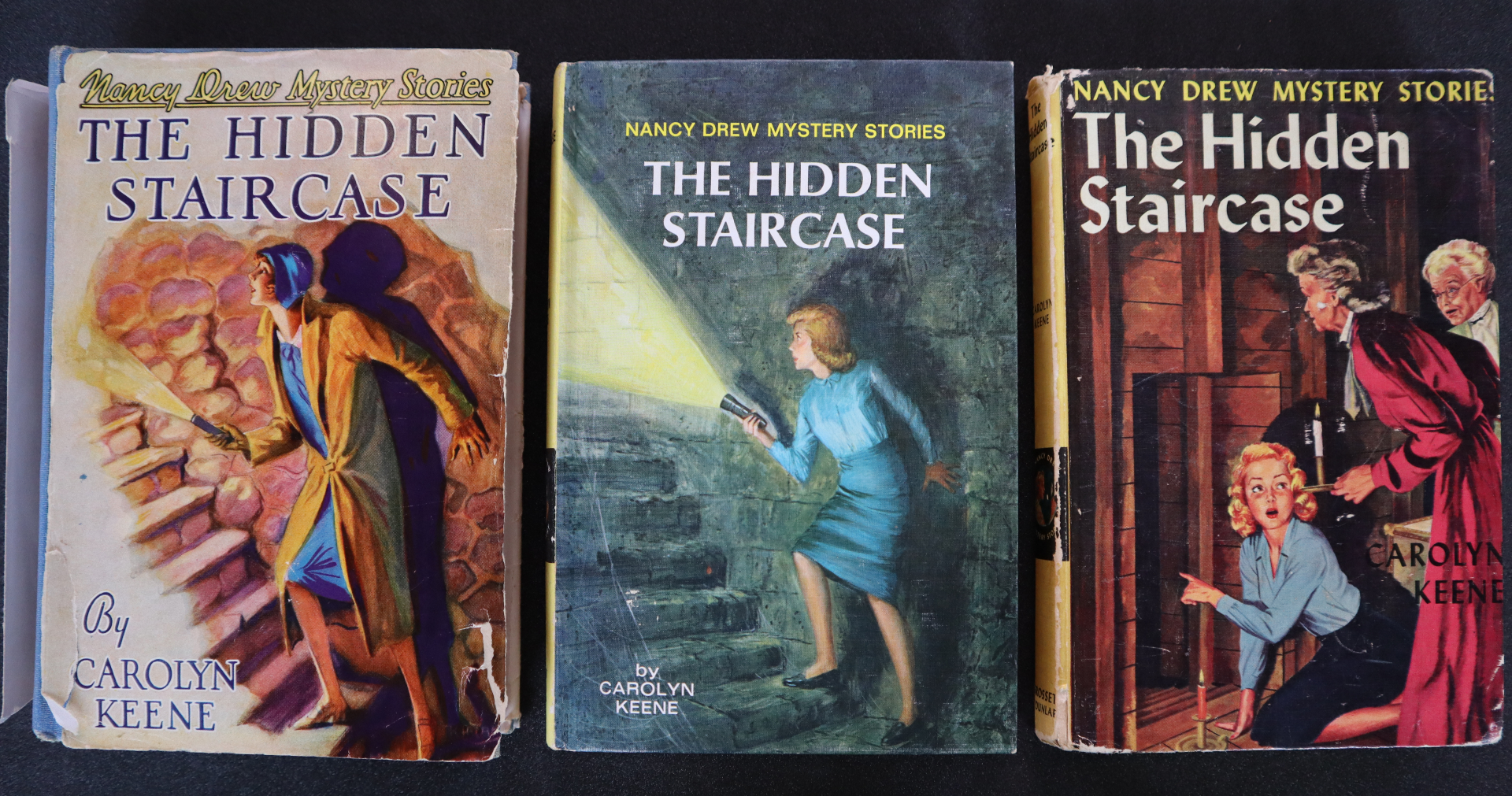

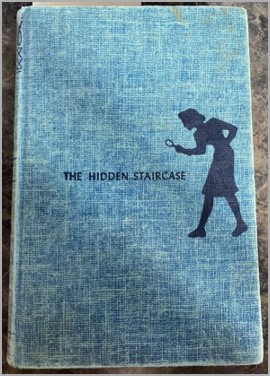

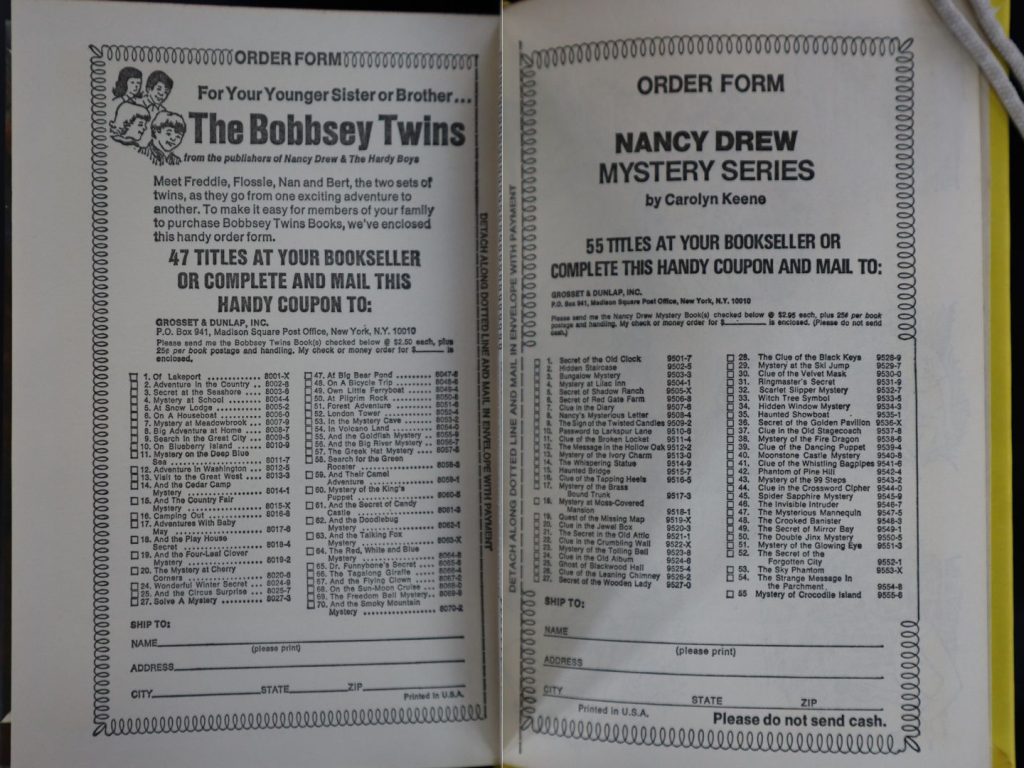

When I first started this research fellowship, I had no clear idea of what I wanted my topic to be. But when I started looking at books in the Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature, I ended up finding an old Nancy Drew book. I remembered these books well from my own childhood, and when I looked at the oldest Nancy Drew book in the library, and saw it was published in 1930, it got me thinking about how uniquely long lasting this series was. This led to my overarching questions of: how did this series last so long? What changes did this series go through to keep up with the times, and make itself relevant with each new generation of readers?

I realized that an important reason these books were able to stick around for so long was due to their adaptability. But at the same time, the consistency in the series is what kept people coming back. The kind of longevity this series achieved is almost impossible to grasp, and to keep going down this line of research I would like to look at several other long running series, to see what kind of developments they’d made compared to Nancy Drew, and to explore what kind of stories the outside of a book can tell.

Women in Wartime by Preslie Price

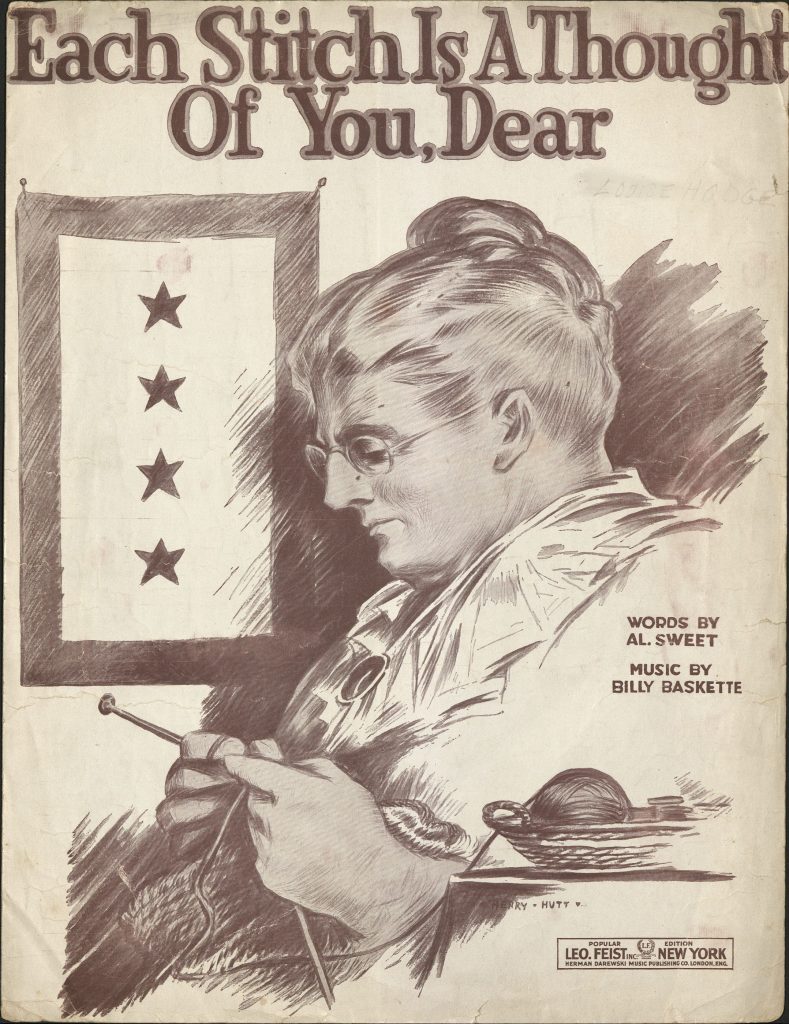

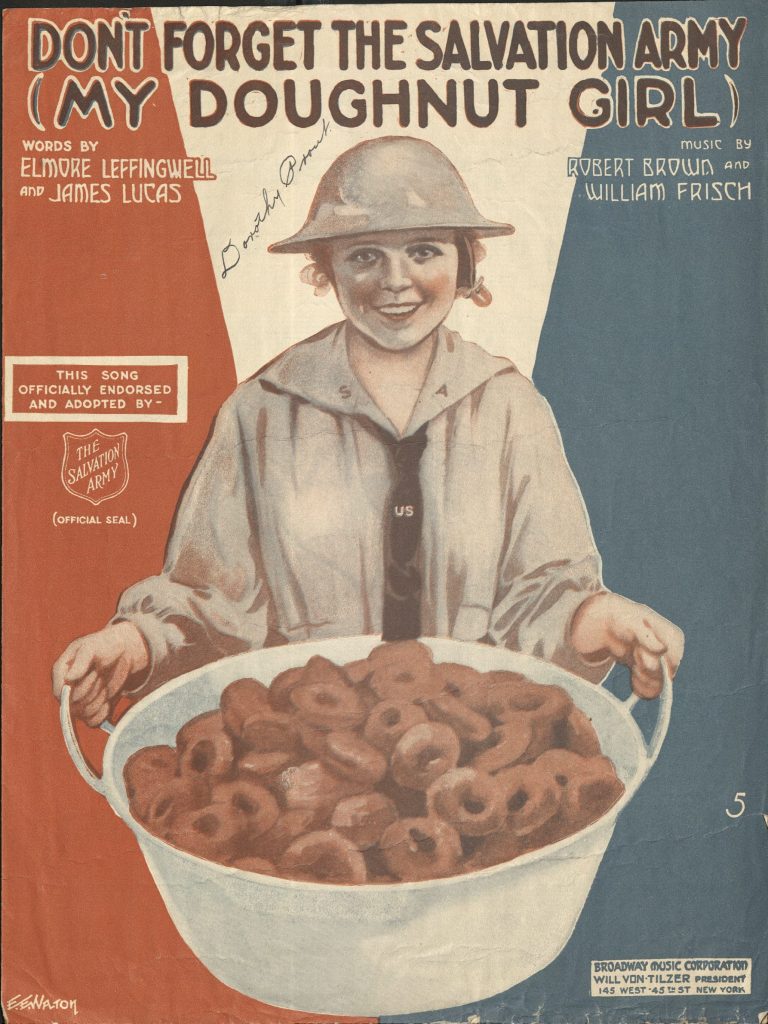

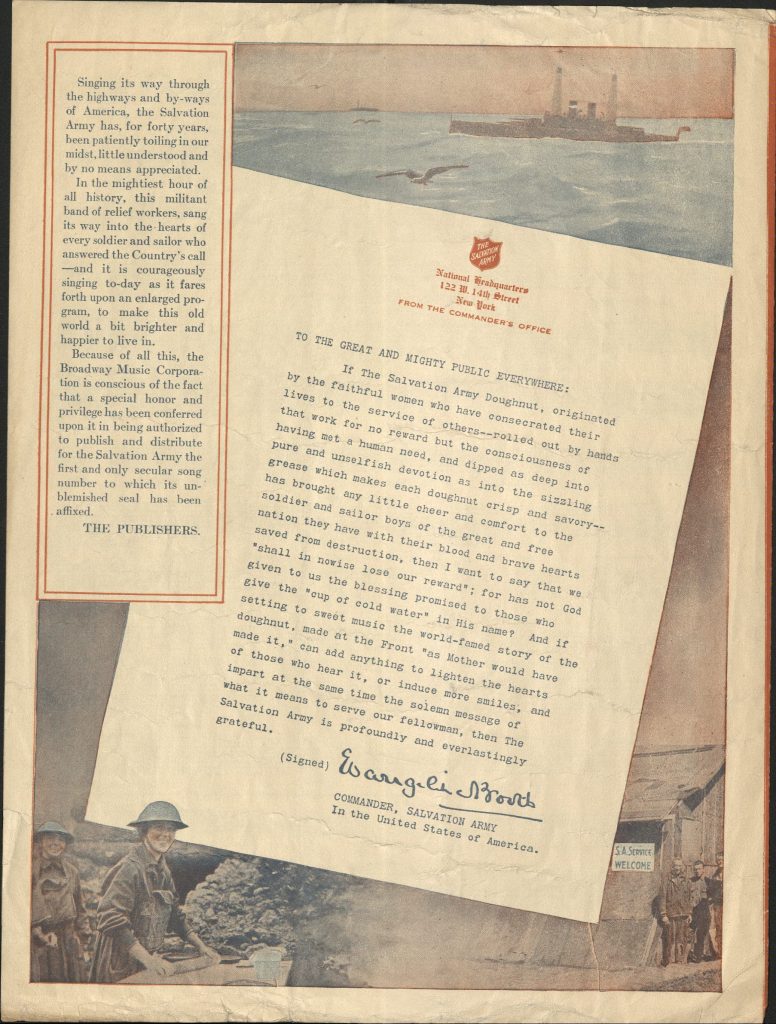

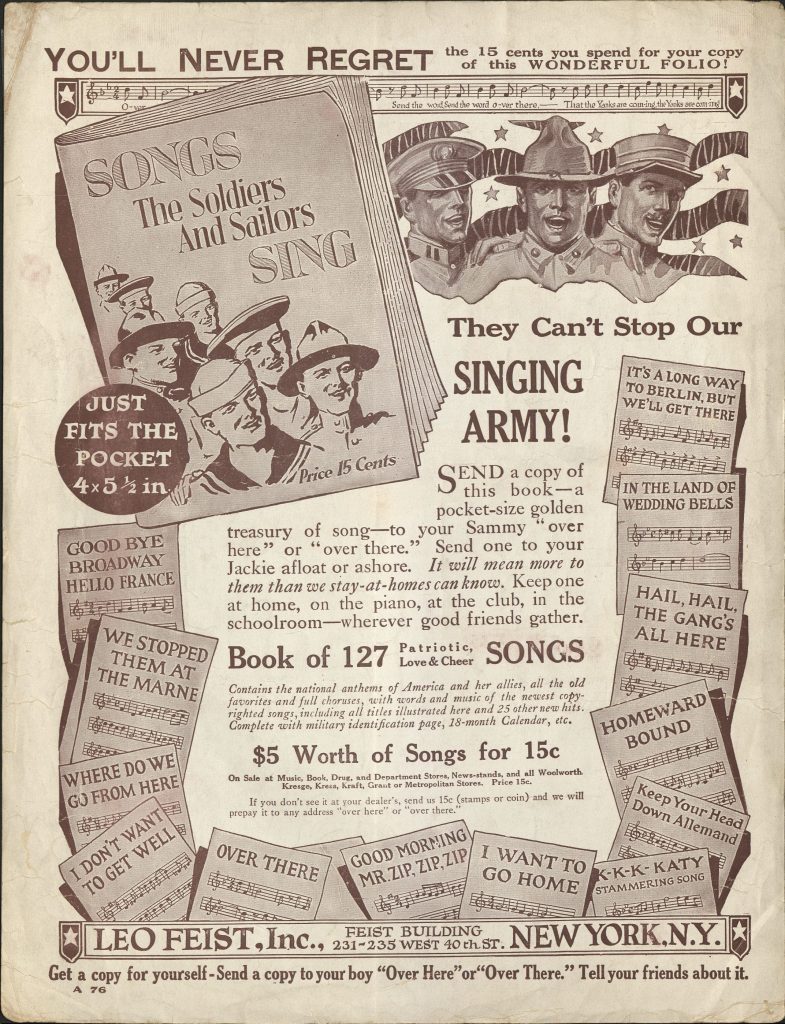

At the beginning of the Discovery Fellowship, I was initially interested in the intersections between music and war during the 20th century. I have always been intrigued by songs with war themes and wanted to see how the pair intertwined before the development of mass media such as radio and TV. After discussing potential options with my mentors, I realized there is a very clear connection between war and song through the medium of sheet music. I investigated the Bernard S. Parker World War One Sheet Music Collection, which boasts a vast array of wartime songs. I discovered the consistent presence of female influence on war efforts, specifically through the propaganda tactics of the cover art, lyrics, and advertisements throughout the sheet music.

My observations about gender roles and women aiding war efforts brought me to two overarching research questions. The first is: how do gender roles/the role of women shift and evolve from WWI through other wars of the 20th century? The second is: how does the role of music as a means of propaganda change? An example would be comparing female-focused propaganda efforts in other wars such as Rosie the Riveter in WWII (she is shown as empowered yet still fits an ideal image of female beauty). On the music front, I would invest time in researching how wartime music evolved and how the use of radio affected cultural sentiment surrounding war. I would also be eager to discover the evolution of protest/anti-war sentiment specifically during the Vietnam war and where those foundations initially developed.

[In the image above, from left: From left, Neil Weijer, Discovery Fellows Preslie Price, Carly Achinapura, Morgan Fisher, Popular Culture curator Jim Liversidge, Bridget Bihm-Manuel, and Baldwin Library curator Ramona Capronegro]