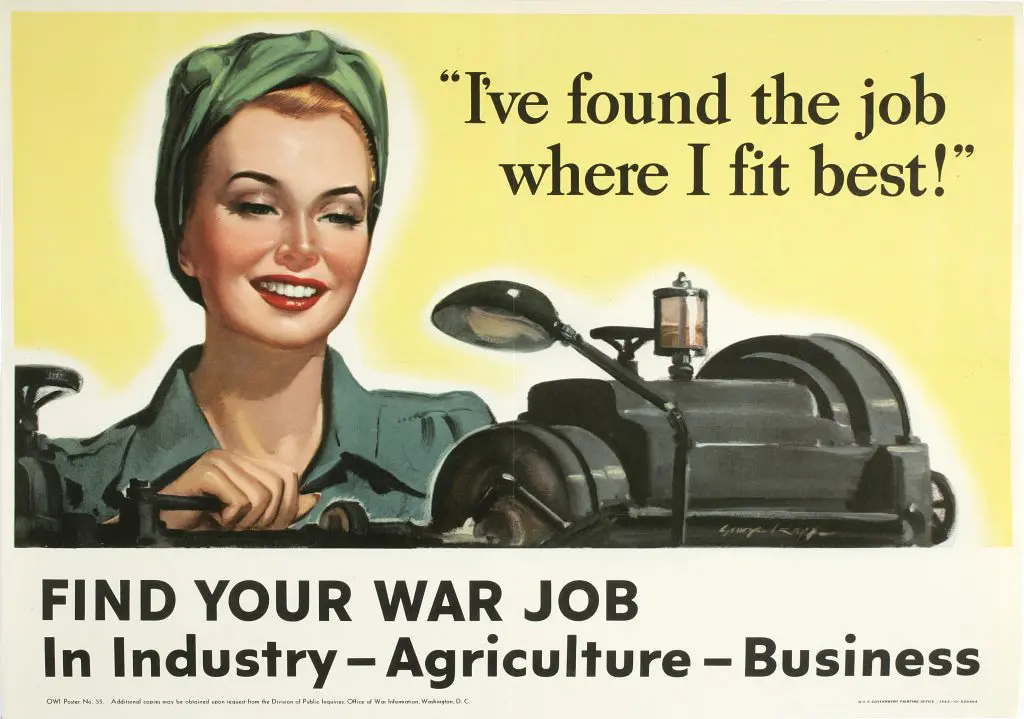

During World War II, the American government placed a significant emphasis on directing female opinion as it pertained to the war effort. They launched a targeted propaganda campaign designed to both inform and entice women, offering them opportunities to take on roles that had previously been devoid of feminine influence.

Despite an unprecedented surge in female labor across various industries deemed crucial to the war effort, it became evident that these newfound responsibilities would be transitory, leaving women with an inaccurate perception of enduring opportunities in traditionally male-dominated sectors.

In the context of this era, the establishment of the Office of War Information (OWI) represented a strategic response to the need for efficient wartime information dissemination. Under the directive of Executive Order 9182 issued by President Franklin D.. Roosevelt, the OWI was tasked with formulating and executing comprehensive information programs to enhance understanding of the war’s status, progress, policies, activities, and aims, both within the United States and abroad.

The OWI’s propaganda wielded profound influence through diverse media channels: press, radio, motion pictures, and other pervasive forms of communication. A primary focus of the OWI was to garner female approval and active participation in the war effort. To explore this unique historical context, this research leverages preliminary investigations conducted within the archives of the Office of War Information. These archives encompass a wealth of primary sources, such as correspondence, memos, historical records, and agendas, offering a rare glimpse into the inner workings of the organization. Notably, the archive includes records pertaining to individuals who served as directors and advisors within the Federal Office, with a significant representation of women in these roles.

Despite its vast historical significance, only a minuscule fraction of the Office of War Information Records, equivalent to 0.01%, has been digitized. In December of this year, I will be traveling to the College Park office of the National Archives in order to conduct an in-depth examination of these records. The primary objective of this research is to shed light on the pivotal role played by female directors within the OWI and to unravel the complexities surrounding female-targeted propaganda and feminine influence in its creation. The study will delve into the specific responsibilities of these female directors, their perspectives on OWI productions, and the potential disparities in opinions when compared to their male counterparts.

By focusing on key figures within the organization, such as Catherine Lanham, who served as the Program Manager for the Security of War Information Campaigns, and Mary Keeler, the Program Manager for the Recruitment of Women, this research will unveil their backgrounds and the remarkable paths they traversed to ascend to leadership positions in a domain historically dominated by men. This exploration of the OWI’s female directors aims to contribute to a nuanced understanding of the dynamics of gender, propaganda, and influence during a critical juncture in American history.