Blog post by Discovery Fellow Aron Ali-McClory

Hello! My name is Aron Ali-McClory, and I am an organizer and student who has been using the University Archives to explore the history of the student movement at the University of Florida, prompted by a manuscript which had been given to me known as Berkeley of the South. The student movement, consisting of intertwining lineages and legacies of student protest and activism, is something that is usually viewed through its most memorable events. My research through the Discovery Fellowship has sought to understand the context in which the student movement exists at UF – especially as there is no widely known or available resource which documents the movement at all its intersections.

The University Archives contains an almost overwhelming array of material on the student movement, much of which has not been digitized, and almost none of which is consistent in format. Many of these materials were housed in ‘vertical files,’ which were topical in nature and could hold any array of documents and ephemera inside. Unlike many archival collections, in which each individual document is organized and listed on an inventory, the contents of each vertical file need to be explored piece by piece, with many documents still in the order they were submitted to the University Archives. From student-made zines to hand-edited messages from the president’s office, student papers and more, I quickly discovered that I had to narrow down my scope if I wanted to begin to do justice to the student movement as I intended, and ended up deciding to center my Fellowship research on Black Thursday for this semester. Black Thursday was a critical event which occurred in April of 1971, and involved a well-supported and militant Black Student Union (BSU) facing off with the cautious presidential administration of Stephen C. O’Connell over demands like establishing an Institute of Black Culture and increasing Black student enrollment.

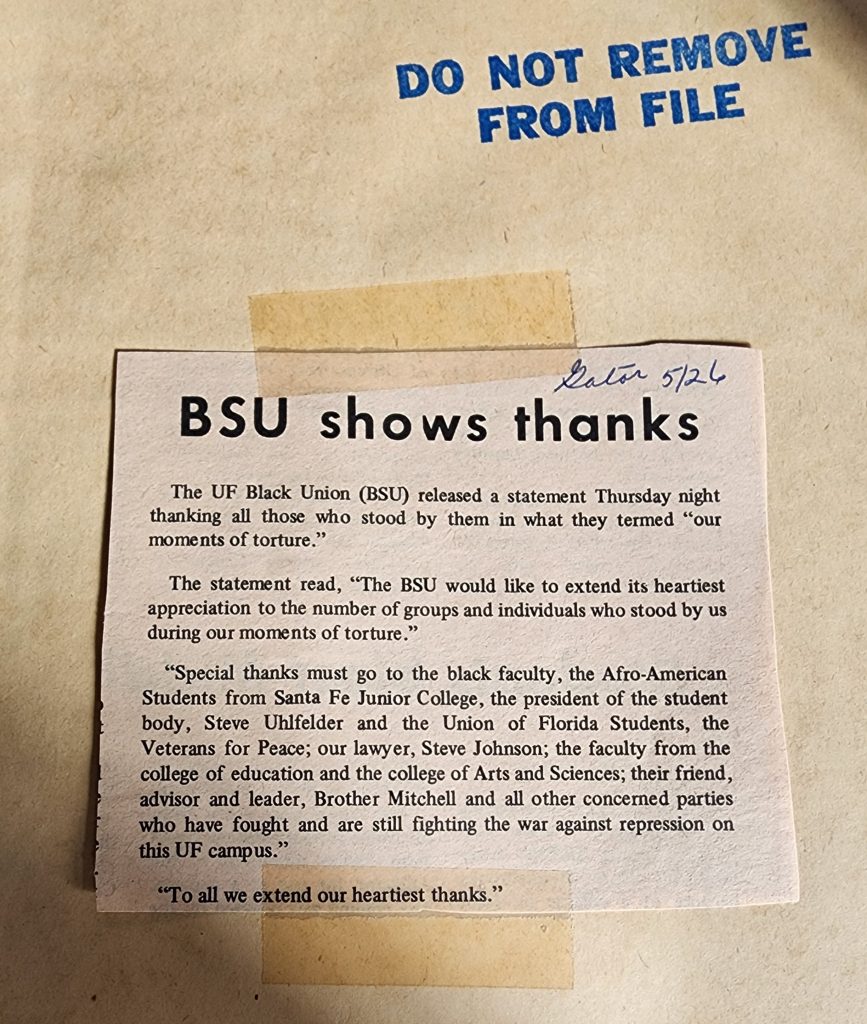

A newspaper clipping found in a vertical file covering a statement from BSU thanking supporters during Black Thursday

What I began to understand as I worked my way through the extensive vertical files is that modern depictions of Black Thursday and the context in which it existed lacked the historical context which could perhaps only be found in the very documents I was reading through. I found that student government, a historically neutral institution at UF, placed itself firmly in support of BSU against the administration, led by insurgent student body president Steve Uhlfelder. Furthermore, I pieced together a narrative spun by the administration that isn’t much talked about, namely their attempt to minimize the voices and actions of those protesting on Black Thursday by garnering large amounts of support from the state government, parents, and parts of the faculty.

After reviewing many of the items in the vertical files, as well as accessing digital editions of the Florida Alligator from the time of Black Thursday, it became clear that only with this kind of thorough review and analysis would one come to understand the student movement in full. As I continue to branch out forward and backwards in time from Black Thursday, I intend to keep a similarly keen eye on how perspective shapes ‘the truth’ as it relates to student protest and activist activities on campus, especially as it relates to administration, community actors, student government, and the students themselves.

Featured image credit: Students march down University Avenue from a newspaper file photo, c. 1971