By Discovery Fellow Ziad El-Rady

As a paper artist, I was drawn to the Special Collections by the treasure trove of pop-up and movable books found in the Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature. As a game designer and D&D Dungeon Master, I knew these 3-D structures had great potential to immerse players into the environment and bring blind and low-vision players to the table. These players have no problems joining in on your average D&D game. Narration that includes details about things like smell and body language help for roleplay, but when battles take place, much of the information is conveyed on drawn or printed maps. My guiding question for this fellowship: How can paper be used to introduce tactile elements and raised surfaces to tabletop games?

While intricate, illustrative pop-ups designed for children brought me to the collections, pop-ups designed for books aren’t made to meet the needs of game spaces, and my focus has since shifted to materials found outside of the Baldwin Library. The maps library has preserved an out-of-use volume of tactile map of Gainesville and UF’s campus, created by the Disability Resource Center in the 1990s. Plain printed material is overlaid with a formed plastic sheet that gives shape to braille, raised paths indicating roads, and bumpy textures representing lakes.

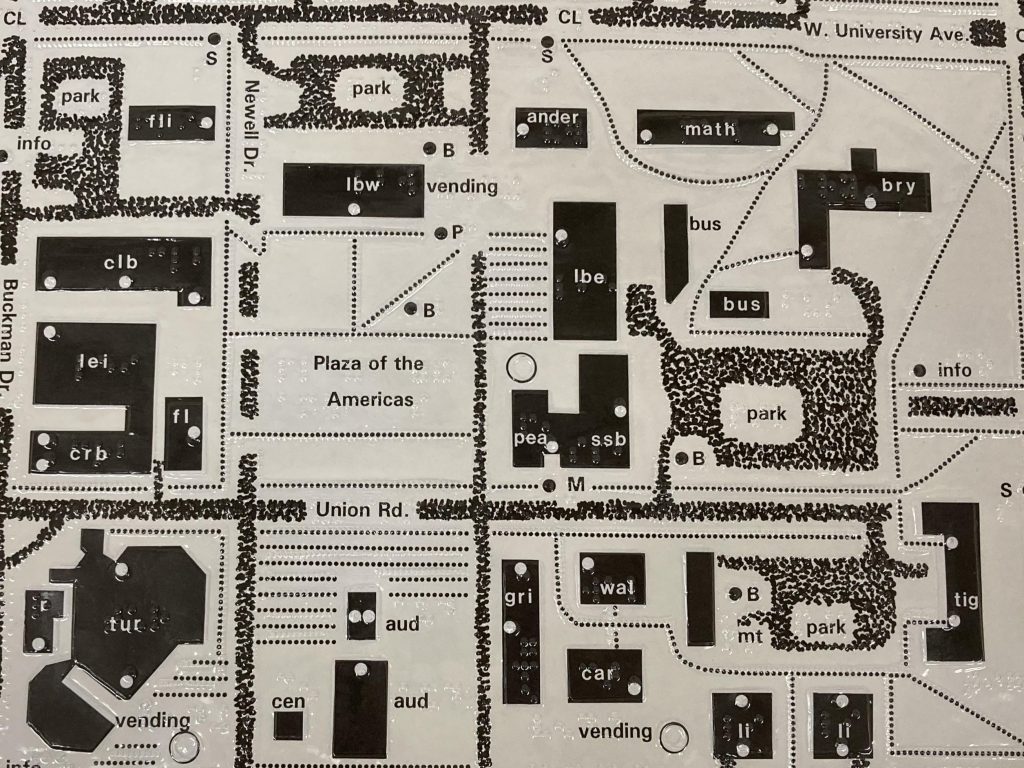

A Braille-overlaid map of the Plaza of the Americas. These maps were both loaned to students and available for reference at library and office desks across the campus in the 1990s.

Understanding what isn’t represented on the map is almost as important as understanding what is; our senses of touch do not understand detail at the same level our eyes do. Therefore, direct translation of a map’s visual information into tactile information is unhelpful. I consider this source as I create paper tactile maps, a process as simple as perforating the page using sharp objects like thumbtacks or pens.

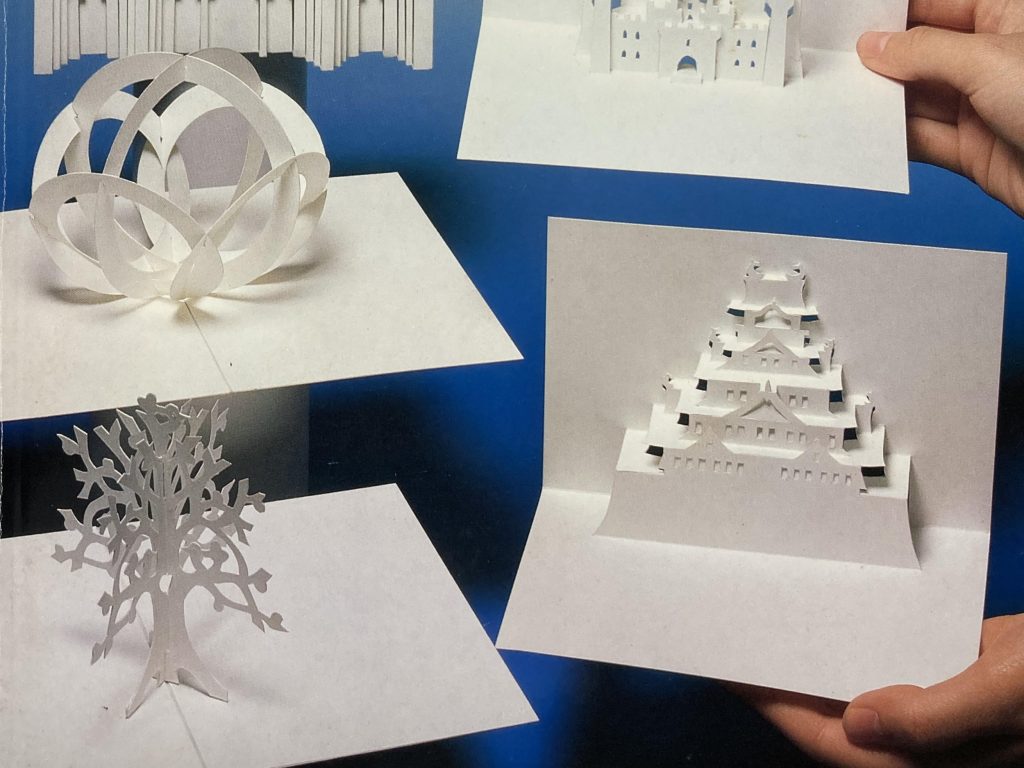

Accessibility has many different meanings. One of paper’s strengths over something like 3-D modeling is its widespread accessibility through its low cost and ease of access. To play towards this strength, techniques that can be done with readily available materials are my priority. A cutting mat, cardstock, and a craft knife are the only things necessary to begin creating Origami/Origamic Architecture (OA), and the results can be impressive. Cutting, scoring, and delicately folding the cardstock on the crease line is all that’s necessary to bring the structure into the third dimension.

Chatani’s paper models include structures and standalone objects. The terraced surfaces of fortifications would lend themselves to playable structures on a game board.

Masahiro Chatani’s Origami Architecture: American Houses Pre-Colonial to Present (1988) offers an introduction to the art form as well as specific patterns designed to recreate American architectural styles. I’ve found OA’s artistic capabilities enchanting, but at a more practical level, it represents a direct way to bring buildings and elevated ground to more tabletops. If this is my aim, then creating a basic guide for the process only makes sense, and Chatani provides a great starting point in his pattern/template creation process. During the latter half of this fellowship, I hope to gain a better understanding of the process by creating patterns of my own.

Featured Image credit: A prototype paper model of a castle with a wizard minifigure (Ziad El-Rady)