This post comes to us from Discovery Fellow Natalie Triana

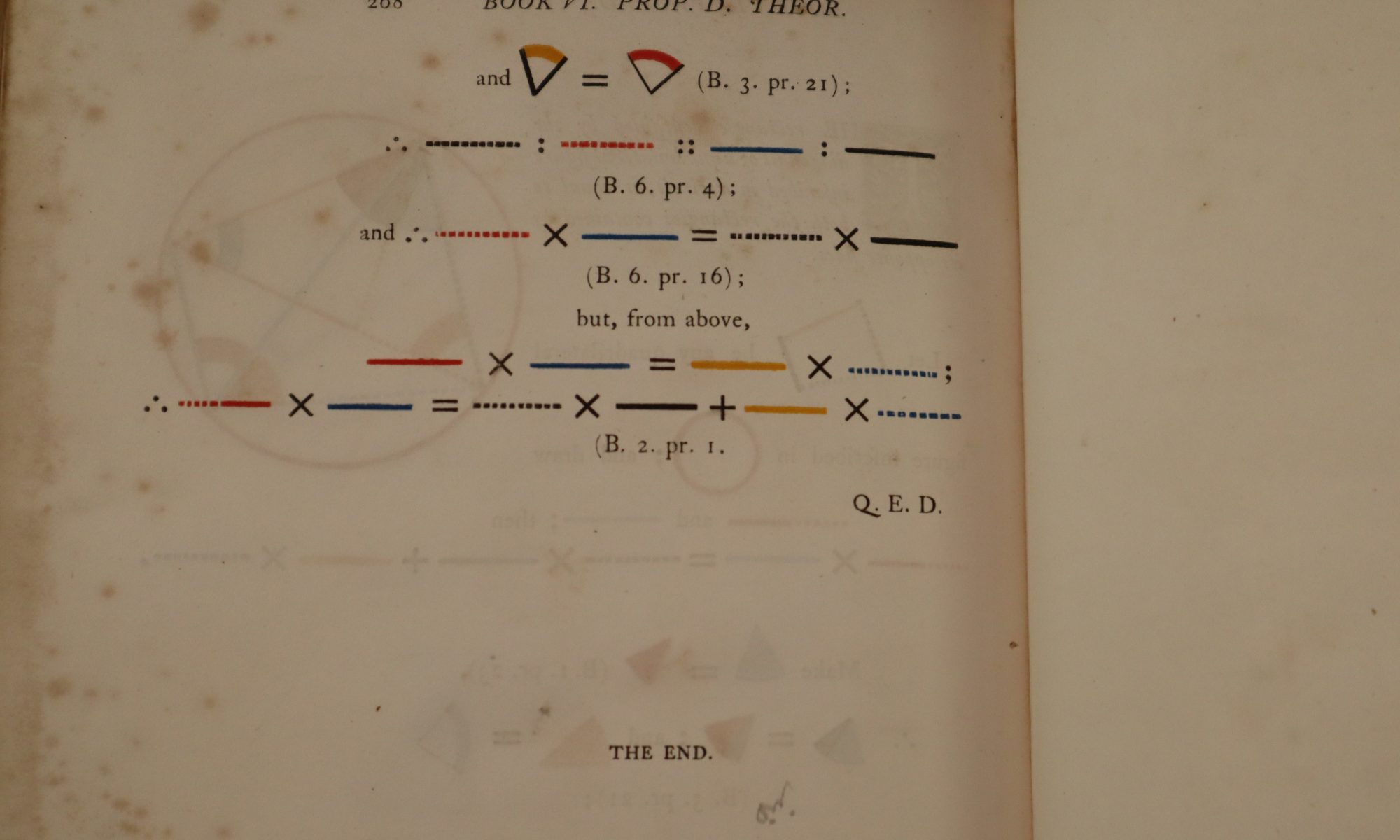

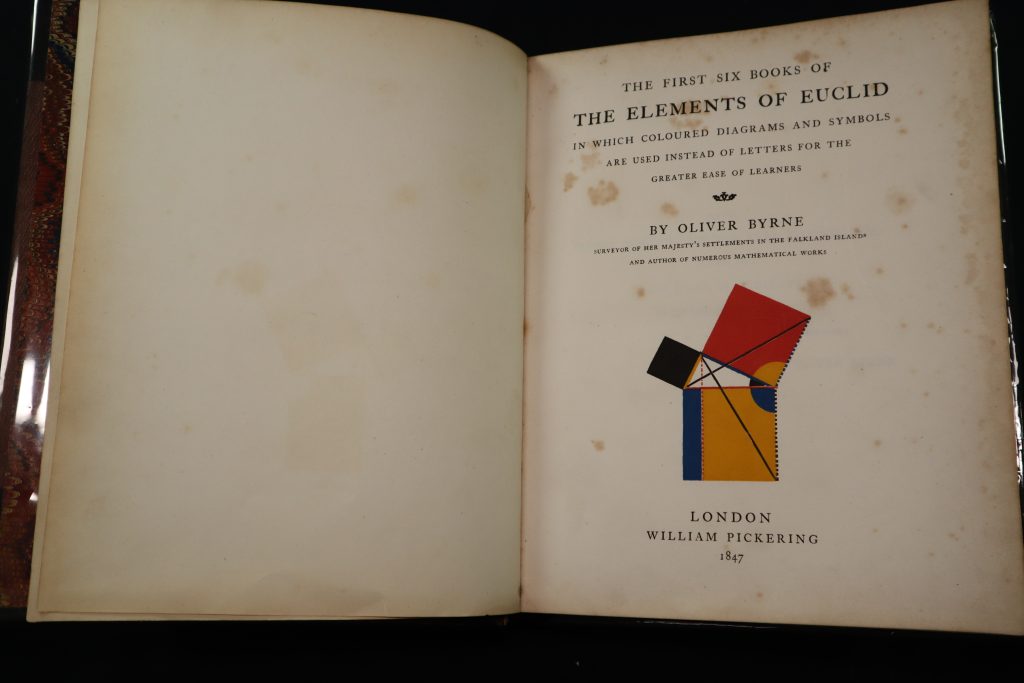

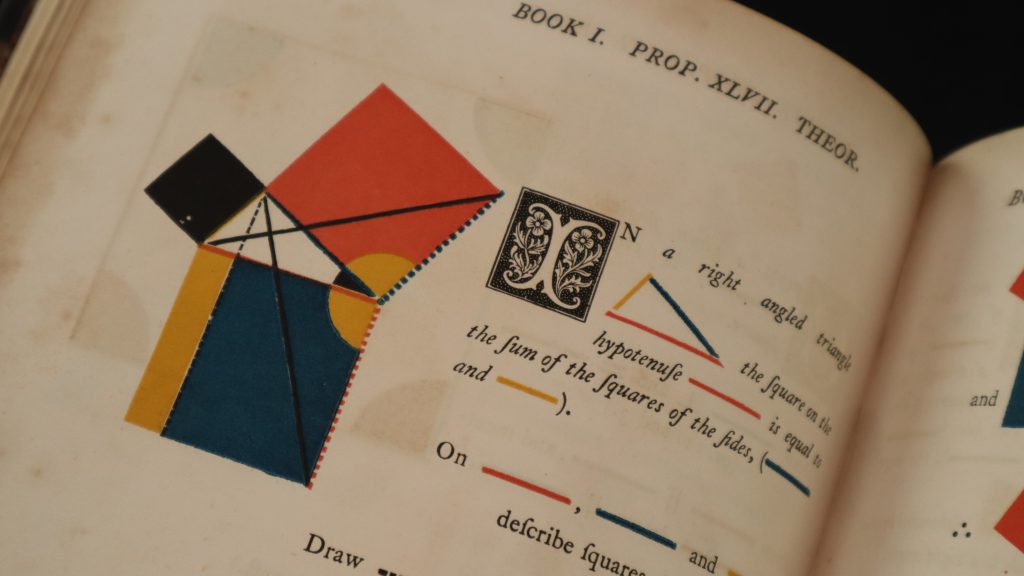

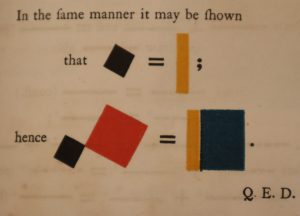

The time I have spent as a Discovery Research Fellow this semester has been nothing short of fulfilling. I was able to dive into the history of the conservation movement, explore new questions about people’s environmental values, and gained an even greater motivation for pursuing these topics in the future. As a bonus, I was able to spend my time in the Special & Area Studies Collection reading room in Smathers Library –– UF’s most stunning library (in my personal opinion, at least).

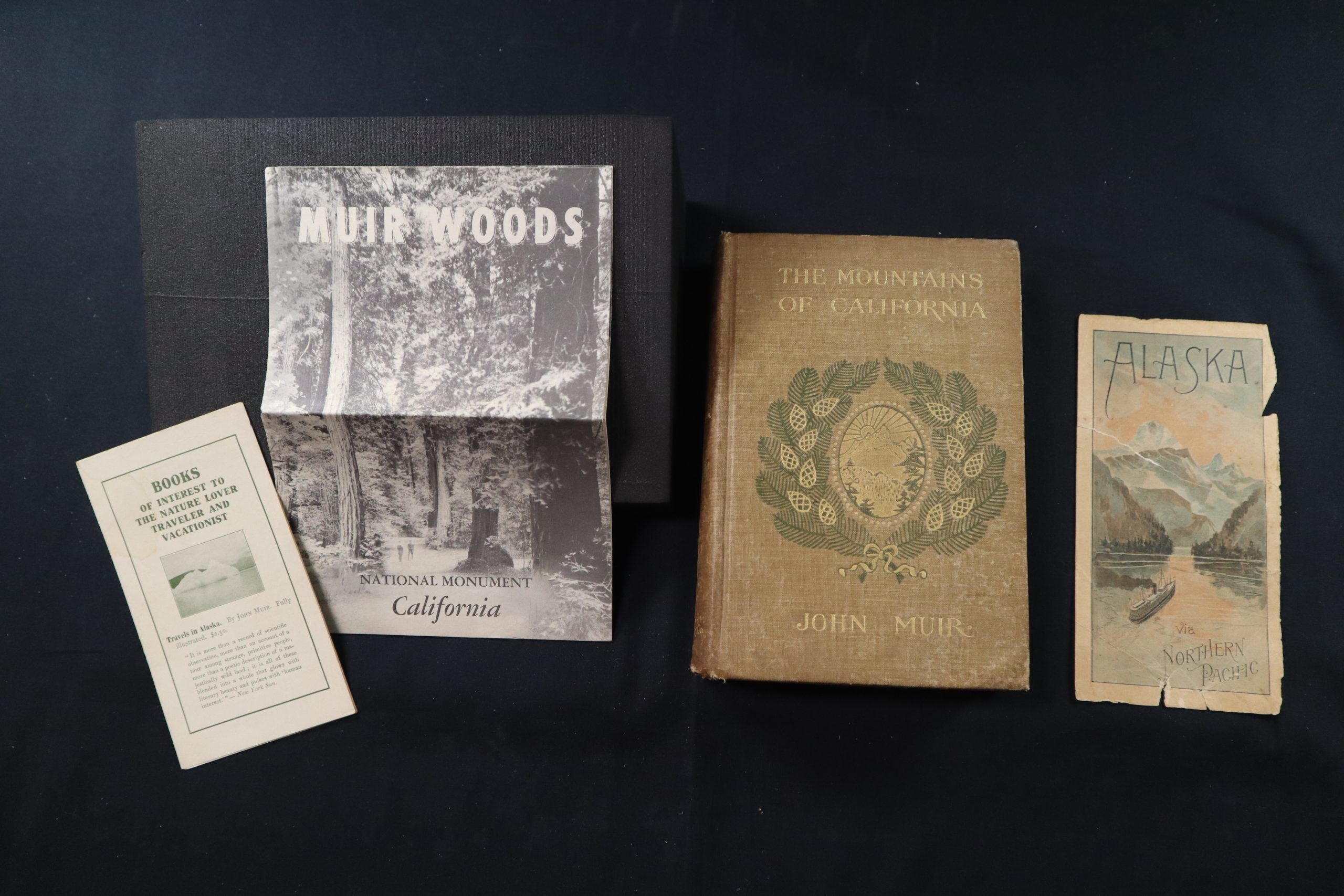

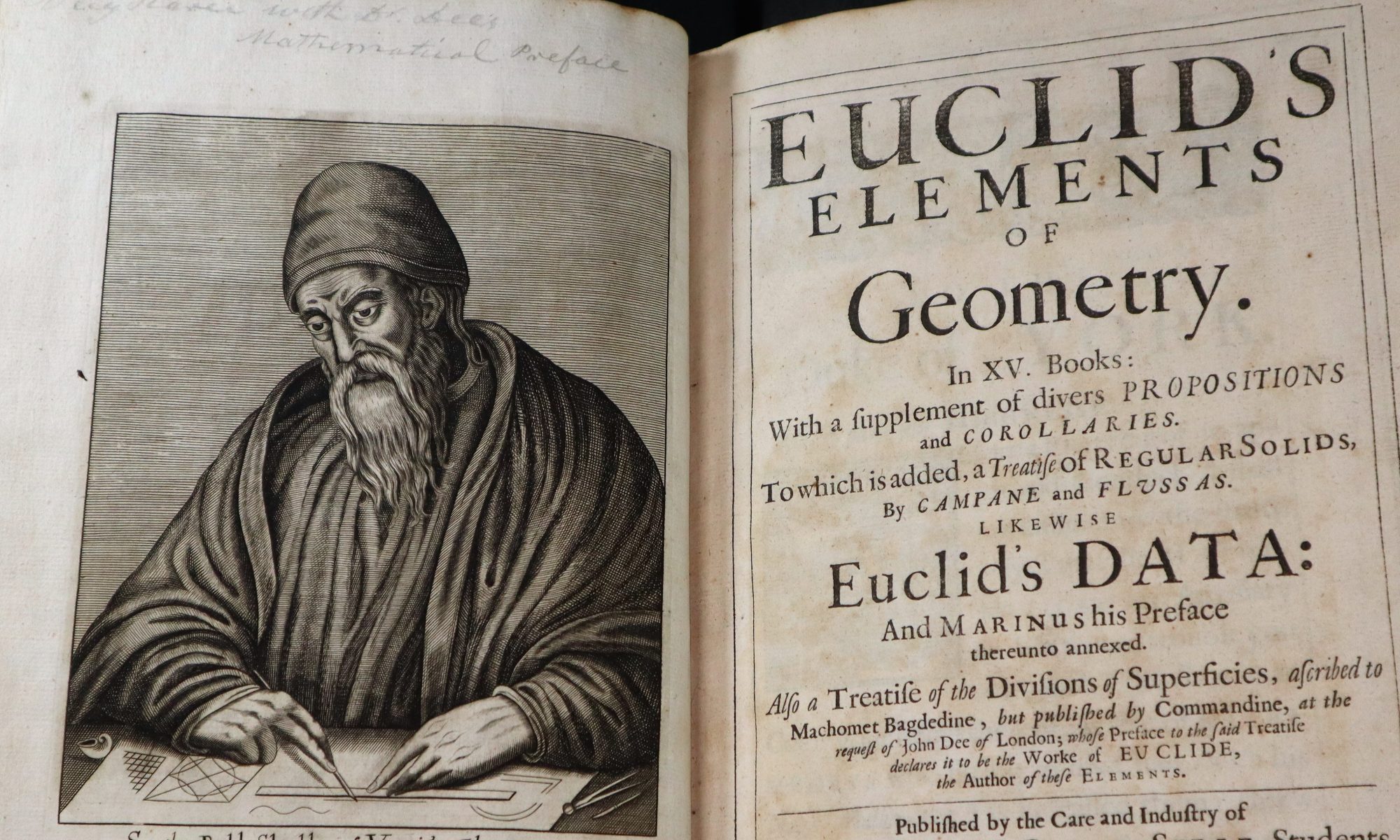

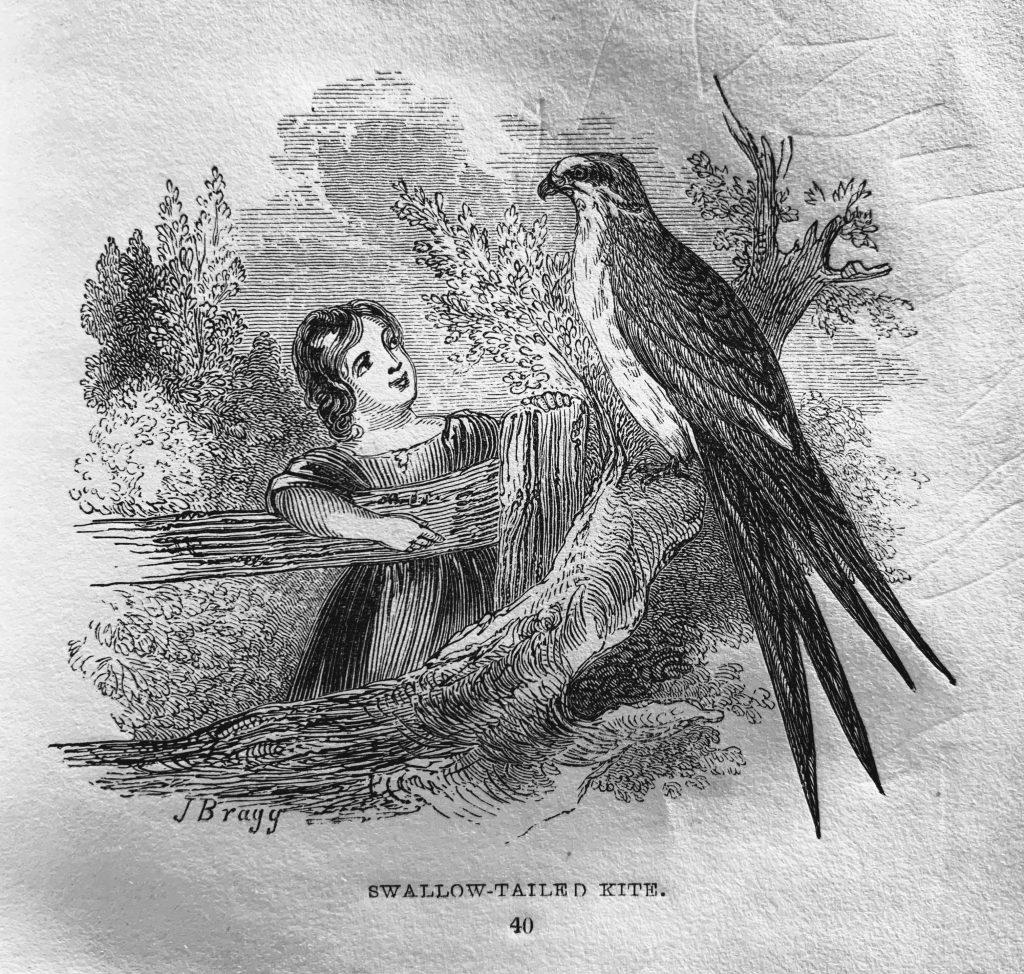

As I read books from early environmentalists, such as William Bartram, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir, I noticed differing perspectives regarding the value of nature in relation to humans. Authors like Thoreau and Emerson argue for nature’s intrinsic value, whereas others discuss the “uses” nature provides to human beings. These contrasting ideologies reaffirm the concepts I was learning in one of my academic classes this semester, which questions why humans act (or don’t act) on their environmental values.

In this class, I learned that many people are incentivized to act sustainably because nature serves a function to us (food, recreation, economic prosperity, etc.). Unfortunately, the downside to this thought process is that our emphasis on nature’s “use” perpetuates the notion that it is inferior to humans and therefore must benefit us to be valued. This causes many people to overlook endangered species and ecosystems that may appear useless or unattractive to the human eye. By examining how different authors view nature’s value, I hope to reexamine the way environmentalists communicate the need for climate action to a general audience. In the future, I would like to see environmentalism shift from an egocentric perspective to a biocentric perspective, where people can appreciate the environment not only for its services but for its mere existence.

Overall, this research fellowship has inspired, intrigued, and informed me beyond what I expected. In the future, I will take the skills that I learned, such as conducting individual research, exploring areas of interest, and knowing how to find materials in a library collection, with me to law school and beyond. This opportunity has allowed me to become more well-versed in environmental literature and in archival research as a whole.